India's Plan to Create the World's Longest River Costs $168B

Published on by Water Network Research, Official research team of The Water Network in Government

A river-linking engineering project would create a waterway almost twice as long as the Nile.

The Indian government is pressing ahead with a controversial plan to create what would effectively be the world's longest rivers network of waterways that, when completed, would measure approximately 7,800 miles in length — almost twice as long as the river Nile.

The Indian government is pressing ahead with a controversial plan to create what would effectively be the world's longest rivers network of waterways that, when completed, would measure approximately 7,800 miles in length — almost twice as long as the river Nile.

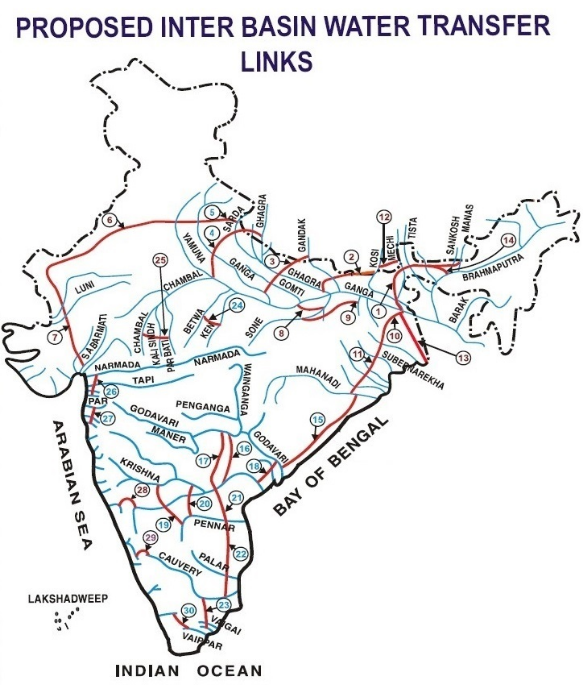

The plan is called the Inter Linking of Rivers Project, or ILR. If completed, it will link 30 rivers — 14 in the Himalayas and 16 in peninsular India — through the construction of 30 canals and 3,000 small and large reservoirs. The idea is to combat both droughts and flood by transferring water from areas where there's "surplus" to those where it's deficient, in the process creating 86,000 acres of arable land and providing the means to generate 34,000 megawatts of hydro power.

The plan has had a very long gestation. In 1858, Arthur Thomas Cotton, a British military engineer, proposed navigable canal links between major rivers to serve East India Company ports and address recurrent droughts. In 1972, Indian politician Kanuri Lakshmana Rao floated a 1,600-mile canal to transfer monsoon floodwaters. Two years later, a water management expert by the name of Dinshaw J. Dastur suggested a series of such canals to improve irrigation.

In the 1980s a new agency, the National Water Development Agency, was created under the country's Ministry for Water Resources to examine the feasibility of the concept. Its website is predictably bullish on the plan: "One of the most effective ways to increase the irrigation potential for increasing the food grain production, mitigate floods and droughts and reduce regional imbalance in the availability of water is the [transfer of water] from the surplus rivers to deficit areas," it says.

"If we can build storage reservoirs on these rivers and connect them to other parts of the country, regional imbalances could be reduced significantly and lot of benefits by way of additional irrigation, domestic and industrial water supply, hydropower generation, navigational facilities etc. would accrue."

The idea's fortunes have waxed and waned over the decades, but appear to have been given a shot in the arm with the election in 2014 as Prime Minister of Narendra Modi, who declared during his campaign that the "dream of linking rivers is our dream as well. This can strengthen the efforts of our hard-working farmers."

As a result, the project now seems closer to fruition than ever. New Scientist reported last week that work on the pilot link between Ken and Betwa rivers in northern and central India is "likely to start any time soon."

The National Water Development Agency has completed detailed project plans for it and two other initial links: between Daman Ganga and Pinjal rivers in western India, and Par and Tapti rivers in western and central India. And the magazine reports that a feasibility report of a fourth link between three Himalayan rivers — Manas, Teesta and Ganges — is in the final stages of preparation.

There's just one small problem. The whole concept has been vigorously and seemingly almost universally panned. It has been described as "disastrous", "not viable," "horrifying and ill-planned" and "a social evil, economic evil."

The criticism is not just over the likely price tag, officially estimated at $168 billion — although "being a project that will take decades to complete, serious cost overruns can be expected." Nor is it solely over the estimated 1.5 million people who will be displaced from their homes. It's also about the fundamental premise.

For a start, there is the question of whether a natural waterway can truly be described as having "surplus" water. Latha Anantha of the River Research Center explained that, "A river has a natural course and for years it has been following that. Who are we to say it has a surplus and it has a deficit? The river will carry as much as it can." Furthermore, changing river dynamics on a large scale can have significant ecological impacts, by, for example, reducing sediment supply and causing coastal and delta erosion.

The Indian government is pressing ahead with a controversial plan to create what would effectively be the world's longest river, a network of waterways that, when completed, would measure approximately 7,800 miles in length — almost twice as long as the River Nile.

The plan is called the Inter Linking of Rivers Project, or ILR. If completed, it will link 30 rivers — 14 in the Himalayas and 16 in peninsular India — through the construction of 30 canals and 3,000 small and large reservoirs. The idea is to combat both droughts and floods by transferring water from areas where there's "surplus" to those where it's deficient, in the process creating 86,000 acres of arable land and providing the means to generate 34,000 megawatts of hydropower.

The plan has had a very long gestation. In 1858, Arthur Thomas Cotton, a British military engineer, proposed navigable canal links between major rivers to serve East India Company ports and address recurrent droughts. In 1972, Indian politician Kanuri Lakshmana Rao floated a 1,600-mile canal to transfer monsoon floodwaters. Two years later, a water management expert by the name of Dinshaw J. Dastur suggested a series of such canals to improve irrigation.

In the 1980s a new agency, the National Water Development Agency, was created under the country's Ministry for Water Resources to examine the feasibility of the concept. Its website is predictably bullish on the plan: "One of the most effective ways to increase the irrigation potential for increasing the food grain production, mitigate floods and droughts and reduce regional imbalance in the availability of water is the [transfer of water] from the surplus rivers to deficit areas," it says.

"If we can build storage reservoirs on these rivers and connect them to other parts of the country, regional imbalances could be reduced significantly and lot of benefits by way of additional irrigation, domestic and industrial water supply, hydropower generation, navigational facilities etc. would accrue."

The idea's fortunes have waxed and waned over the decades, but appear to have been given a shot in the arm with the election in 2014 as Prime Minister of Narendra Modi, who declared during his campaign that the "dream of linking rivers is our dream as well. This can strengthen the efforts of our hard-working farmers."

As a result, the project now seems closer to fruition than ever. New Scientist reported last week that work on the pilot link between Ken and Betwa rivers in northern and central India is "likely to start any time soon." The National Water Development Agency has completed detailed project plans for it and two other initial links: between Daman Ganga and Pinjal rivers in western India, and Par and Tapti rivers in western and central India. And the magazine reports that a feasibility report of a fourth link between three Himalayan rivers — Manas, Teesta and Ganges — is in the final stages of preparation.

There's just one small problem. The whole concept has been vigorously and seemingly almost universally panned. It has been described as "disastrous", "not viable," "horrifying and ill-planned" and "a social evil, economic evil."

The criticism is not just over the likely price tag, officially estimated at $168 billion — although "being a project that will take decades to complete, serious cost overruns can be expected."

The criticism is not just over the likely price tag, officially estimated at $168 billion — although "being a project that will take decades to complete, serious cost overruns can be expected."

Nor is it solely over the estimated 1.5 million people who will be displaced from their homes. It's also about the fundamental premise.

For a start, there is the question of whether a natural waterway can truly be described as having "surplus" water.

Latha Anantha of the River Research Center explained that, "A river has a natural course and for years it has been following that. Who are we to say it has a surplus and it has a deficit?

The river will carry as much as it can." Furthermore, changing river dynamics on a large scale can have significant ecological impacts, by, for example, reducing sediment supply and causing coastal and delta erosion.

Others question the notion of a disparity in river systems. A committee on water reforms, appointed by the Water Resources Minister (who is an advocate of the scheme) argued that, "because of our dependence on the monsoon, the periods when rivers have 'surplus' water are generally synchronous across the subcontinent."

Additionally, as climate changes, there is no guarantee that those regions that receive extra rainfall now will continue to do so in the future — and is, in fact, some reason to believe that they won't be. "What may appear as water deficient today may become water surplus in the future due to climate change," said Sachin Gunthe of the Indian Institute of Technology, Madras. "So, how do you justify inter-linking?"

None of which is to deny the very real water supply issues facing India. It's undeniable that floods are an issue in some parts of the country, while droughts plague others. And a population already touching one billion and expected to rise to 1.8 billion by mid-century will need a lot of water for crops. The question is whether this mammoth undertaking is the way to address those concerns.

Read more at: Seeker.com

Media

Taxonomy

- Irrigation and Drainage

- River Studies

- River Restoration

- Irrigation & Water Management

- River Engineering

- Institutional Development & Water Governance

- Biodiversity conservation

- Flood

- Water Government Officials

- National Water Development Agency

- Ministry of Drinking Water and Sanitation, Govt. of India

- Water

- India

2 Comments

-

The restoration of native ecosystems ( forests, grasslands, wetlands) together with small reservoirs and monitoring are the way to improve water security. This is ancient knowledge borne from experience. Hopefully the debate will recognize this.

-

There are both +ves and -ves to the society, economic growth and ecosystems. I guess the authorities are studying all aspects and taking appropriate decisions. This needs more informed debate, before committing and starting the work.

1 Comment reply

-

Hopefully the authorities engage in a debate in a transparent manner.

-