India Is Suffering One of Its Worst Droughts in Decades

Published on by Water Network Research, Official research team of The Water Network in Social

Two years of poor rains add pressure to manage water better in India

No rain, no water, no choice.

That’s how 26-year-old Vijay Jadhav describes his decision to travel with his family to coastal Mumbai, India’s financial capital, from a parched smallholding more than 400 kilometers (250 miles) further east in Maharashtra state.

The Jadhavs headed to an improvised suburban camp established last month for some of the rural poor streaming into the mega-city to find water. The 3,000 square foot tent has three giant water tanks and houses about five dozen families. The activists who put it up expect at least 1,000 more people in May.

“It became too tough to have to look for water every day,” Jadhav said, as children played in the tent between bundles of clothes and piles of firewood.

“One can manage without food. How can anyone live without water?”

Hundreds of millions of people in India are grappling with one of the nation’s worst droughts since independence, following two years of poor rainfall and the onset of intense summer heat. The upcoming monsoon is expected to bring some relief, but a longer term challenge looms from competition for scarce groundwater and surface supplies among farmers, industries and cities.

The Mumbai camp was set up between factories in the northern suburb of Thane by local political party Shiv Sena. The tent may come down next month if the government’s prediction of a good monsoon turns out to be right—the June to September downpours bring the bulk of yearly showers. India would be in almost uncharted territory if the season disappoints for a third year.

Water Commuters

Drought is affecting everything from electricity generation to sports events in Mumbai—a metropolis of 18 million people—and the surrounding state of Maharashtra. Local officials are mulling steps to force power companies to use recycled waste water. The city’s high court told the Indian Premier League to hold cricket matches outside the state so that water isn’t wasted on pitches.

Some people are forced to commute to get supplies. Vishwas Bhosale, a 55-year-old gardener, said he fills up four 15-liter cans of water at the taps outside Mumbra station in northern Mumbai before taking the train back home to Diva, part of a journey of about 9 kilometers. Many people do the same thing, and ticket collectors waive the fare for humanitarian reasons, he said.

Some people are forced to commute to get supplies. Vishwas Bhosale, a 55-year-old gardener, said he fills up four 15-liter cans of water at the taps outside Mumbra station in northern Mumbai before taking the train back home to Diva, part of a journey of about 9 kilometers. Many people do the same thing, and ticket collectors waive the fare for humanitarian reasons, he said.

“The taps run dry two days a week,” Bhosale said. “There’s been a water cut because of the drought.”

Maharashtra along with Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh, Karnataka, Telangana, Odisha and West Bengal all declared a drought in 2015, prompting the federal government to allot 103 billion rupees ($1.6 billion) of assistancefor states through the National Disaster Response Fund.

Drinking Water

Deficient rains can be devastating as about half of India’s 1.3 billion population is employed in agriculture, which accounts for roughly 18 percent of the nation’s $2 trillion gross domestic product. Over a quarter of habitations in the countryside don’t have enough to drink, according to the government.

The single biggest disbursement from the disaster fund was to the region of Marathwada, which lies an overnight train journey east of Mumbai at the epicenter of the drought in Maharashtra.

The single biggest disbursement from the disaster fund was to the region of Marathwada, which lies an overnight train journey east of Mumbai at the epicenter of the drought in Maharashtra.

Dry farmland and empty reservoirs pockmark the region. One example is the Manjara dam, which is supposed to supply a clutch of towns and small villages in Marathwada. Dead snakes lie at the bottom of the reservoir and egrets walk across the cracked earth.

About 140 kilometers further east in Latur—a city with about as many people as New Orleans—residents are relying on trains to bring in drinking water in 50 tanks of 50,000 liters each. The Jadhav family’s two-acre farm is near Latur.

“In the last three years there was no rain in the catchment area of Manjara dam, which supplies water to Latur,” said local Municipal Commissioner Sudhakar Telang. “This is the main reason we’re facing such a panic situation in the city. On February 22, we stopped piped water supply.”

Latur is now digging trenches to harvest rainwater this year and seeking supplies from other dams to try and avoid a repeat of the current problems, he said.

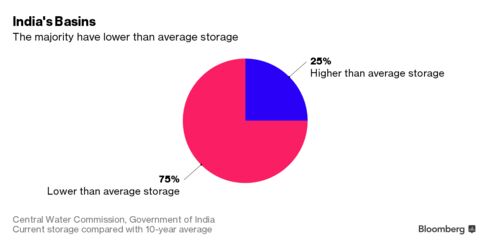

Some 75 percent of India’s basins currently hold less water than the average for the past 10 years, Central Water Commission data show. Storage is about half usual levels in a western region covering Gujarat—home to Ford Motor Co. and Bombardier Inc. factories—and Maharashtra. Across the country, major reservoirs are 79 percent empty.

Some 75 percent of India’s basins currently hold less water than the average for the past 10 years, Central Water Commission data show. Storage is about half usual levels in a western region covering Gujarat—home to Ford Motor Co. and Bombardier Inc. factories—and Maharashtra. Across the country, major reservoirs are 79 percent empty.

The water crisis should ease later this year. Forecasters expect the first good June-to-September monsoon since 2013 as changes in equatorial waters in the Pacific Ocean lead to weather patterns that spur downpours. This so-called La Nina phenomenon would follow an El Nino that hurt rainfall last year.

People filling vessels from a ground water tap in Latur, Maharashtra, India.

Photographer: Dhiraj Singh/Bloomberg

Modi’s Task

The bigger challenge for Prime Minister Narendra Modi is how to manage India’s water demand in the long term, as he tries to transform the country into a manufacturing hub and sustain the fastest pace of expansion among major economies. He said last month in a national radio address that the nation should strive to save every drop.

India is one of the world’s biggest users of groundwater, and the World Resources Institute estimates more than half of the nation faces high water stress. A 2009 study by the University of California, Irvine, and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration showed groundwater depletion in northwestern India from 2002 to 2008 was equivalent to a net loss triple the capacity of Lake Mead, the largest manmade reservoir in the U.S.

India is one of the world’s biggest users of groundwater, and the World Resources Institute estimates more than half of the nation faces high water stress. A 2009 study by the University of California, Irvine, and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration showed groundwater depletion in northwestern India from 2002 to 2008 was equivalent to a net loss triple the capacity of Lake Mead, the largest manmade reservoir in the U.S.

Modi’s agenda includes reviving a 30-year-old plan to link Himalayan and peninsular rivers to channel water to deficient basins. In February, the administration raised the budget for the water ministry—which oversees initiatives such as irrigation—by 70 percent to 125 billion rupees, and announced 60 billion rupees on improving groundwater management.

Even so, officials have yet to clamp down on excessive groundwater extraction, patchy metering, theft and below-cost or unbilled supplies, which are stoking over-exploitation.

“This year’s water crisis is a lesson,” said Prashant Goswami, director and climate scientist at CSIR-National Institute of Science, Technology and Development Studies in New Delhi. “We need to manage our resources.”

Vijay Jadhav, the young man in the Mumbai camp, said he’d tried to do just that at his farm by building water storage structures two years ago—but then watched aghast as the rains failed. He plans to stay in the tent until the monsoon, and then go home.

“One can manage without food,” he said. “How can anyone live without water?”

Source: Bloomberg

Media

Taxonomy

- Groundwater

- International Disaster Planning, Preparedness and Response

- Ministry of Drinking Water and Sanitation, Govt. of India

- India

1 Comment

-

Until and Unless the Modi Govt. restrict the area of high water consuming crops ( sugarcane, rice, etc) like that of Opium, the water crisis in India will continue to expand exponentially