Ancient Mauryan Technology Brings Water, Hope to Dry Magadh in Bihar

Published on by Water Network Research, Official research team of The Water Network in Technology

Inspired by a college professor, villagers in the south-central part of Bihar donated money, built traditional channels and embankments to irrigate fields and ease farm woes.

Ancient Mauryan engineering has brought water back to the undulating and rocky terrain of Magadh, the grain bowl of Bihar that had turned almost entirely arid because of abortive modern irrigation policies.

The Magadh region, comprising 10 districts in south-central Bihar, was reeling from its worst water crisis over a decade ago, forcing farmers to board trains to distant cities such as New Delhi and Chandigarh and work there as migrant labourers.

The Magadh region, comprising 10 districts in south-central Bihar, was reeling from its worst water crisis over a decade ago, forcing farmers to board trains to distant cities such as New Delhi and Chandigarh and work there as migrant labourers.

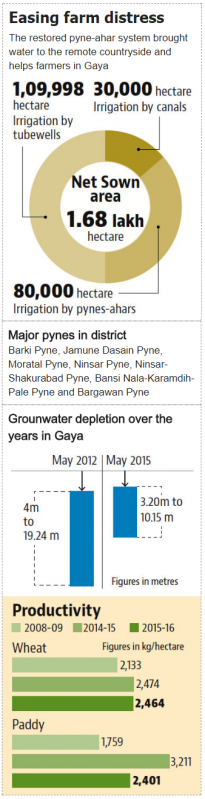

Rainfall was scant, people had long abandoned traditional reservoirs that caught and stored rainwater run-off, the water table in aquifers had depleted from overuse, and modern irrigation canals covered only a small area.

Gaya itself was a modern nightmare as most of its ponds overflowed with garbage. The water table had dipped below 200 feet, and taps and tube wells had gone dry. The water crisis was so acute that people sold their houses in posh localities at throwaway prices. The government promised to build a 100km canal from the Ganga, but the project failed.

The crisis looked irreversible but Rabindra Pathak, who taught Pali and Sanskrit at a college in Arwal, was certain that the answer lay in the long-forgotten and crumbling aqueducts and water reservoirs that irrigated the fields and fed ancient India’s most glorious empire.

He pored through old books and scriptures, and found that reviving the dilapidated network of pynes and ahars was the lone solution.

Pynes are channels carrying water from rivers. Ahars are low-lying fields with embankments that act as water reservoirs. This combined irrigation and water conservation system dates back to the Mauryan era that flourished in Magadh 2,000 years ago.

Pathak founded the Magadh Jal Jamaat (MJJ) in 2006, a network of individuals working to revive the neglected pynes and ahars. “There was no other way to solve the recurring water crisis threatening to turn the region arid. Reckless use of tube wells for irrigation without adequate recharge complicated the scenario,” he said.

Convincing people to participate was not easy in a fragmented society, where nobody was willing to part with an inch of land.

But Pathak was determined to do the unthinkable — bring water to the area. He got ample help from his professor-wife, Pramila, and trader Prabhat Pandey.

They persuaded villagers to form committees and donate anywhere between Rs 100 and Rs 1,000, depending on the size of agricultural plots they owned, and revived the 125-km Jamune Dasain pyne and 159-km Barki pyne. These two complex channels, rebuilt with help from social worker Chandra Bhushan, brought water from Falgu, a tributary of the Ganga.

The impact was instantaneous and miraculous. About 150 villages along the Jamune-Dasain pyne and around 250 villages along the Barki canal have been able to irrigate their fields for the kharif and rabi (monsoon and winter) crops, and grow vegetables, pulses and oilseeds as well.

The farm distress eased significantly. Life changed for marginal farmer Jairam Bhagat, who wanted to kill himself when his paddy crop failed in 2007, after he met volunteers of the Magadh Jal Jamaat. He joined the group, discarded plans to return to Chandigarh where he worked as a plumber, and contributed his mite for the irrigation system.

Read the full article at Hindustan Times

Media

Taxonomy

- Agriculture

- Sustainable Agriculture

- Irrigation

- Irrigation and Drainage

- Irrigation & Water Management

- Agriculture & Forestry

- Irrigation Management

- Sustainable Agriculture

- Agricultural Technology

- India

1 Comment

-

Hello it is the artificial intelligence that has killed the market economy by regulation, standard, compliance and law, it is artificial intelligence that has rebuilt an economic system of yesteryear.

Again we reverse to find solutions that have already existed in the past